KN95 masks distributed in SA fail the stipulated safety thresholds – Study finds

24th December 2020

Covid fears trigger rush on unproven animal drug

13th January 2021Sunday Times Daily – Claire Keeton – 07 January 2021 – 18:53

Image: Sergey Chayko

Oxford-AstraZeneca will be easier and cheaper to roll out in SA than many of the top contenders

When health minister Zweli Mkhize announced on Thursday that the first Covid-19 vaccine SA will get is the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, it was an obvious first choice from the top contenders.

Most importantly, the science shows it works (70.4% efficacy) and it is safe. No severe side effects have been reported in ongoing clinical trials.

Half of the nearly 24,000 participants enrolled in the four randomised controlled trials taking place in Brazil, SA and the UK, from April to November 2020, have already got the vaccine.

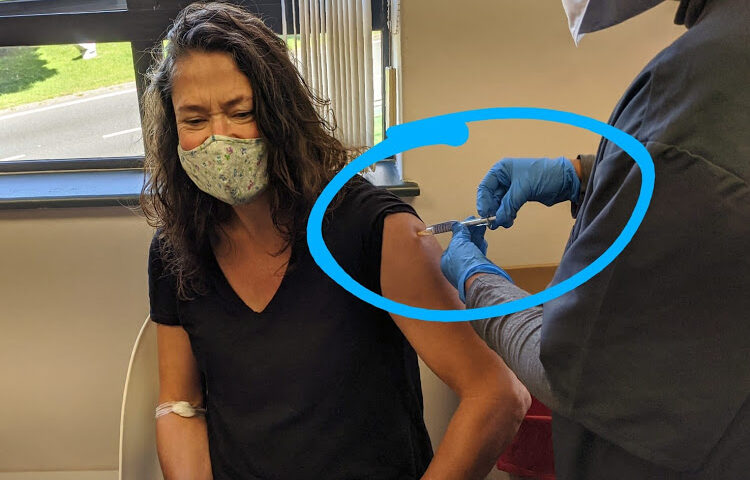

As a vaccine volunteer on this trial, participating through the well-organised site at the UCT Lung Institute, I could be one of them — and I could be biased in its favour.

But it is clear that this vaccine will be easier and cheaper to roll out in SA than many others, such as the genetic vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, which need to be stored in freezers.

This vaccine can be stored in a fridge and will cost only about R110 only for the two shots required for protection against coronavirus, making it far cheaper than other leading candidates.

In December, scientists published a paper in the international medical journal, The Lancet, which found the vaccine “could contribute to the control of the Covid-19 pandemic” if widely deployed.

Processes have happened in parallel, which has really sped things up.

This was the first peer-reviewed data to be published on the frontrunner vaccines, and it was based on an interim analysis of the data.

The ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (its trial name) provided 90% protection to participants receiving a low dose, followed by a standard dose. Efficacy was 62% among participants receiving two standard doses, the researchers found.

All 10 participants hospitalised for Covid-19, 21 days after the first dose, did not get the active vaccine being tested but got the placebo (in the control arm).

The paper’s third author Prof Shabir Madhi, a vaccinologist at Wits University, described the interim findings as “stunning successes” at the time of publication.

“All this has happened in a brief period of less than a year. It normally takes up to 10.5 years from human trials to licensing of a safe and effective vaccine,” he said in an interview.

“That’s not to say any shortcuts have been taken. It’s because processes have happened in parallel, which has really sped things up.”

The higher efficacy among the participants who got lower doses could relate to the way the body mounts its defence, he said.

Image: ASENATHI NXANA

In an interview with the BBC, Oxford University vaccinologist Prof Sarah Gilbert said: “That [result] was unexpected, and we are looking into the reasons for that. We are looking at the immune responses in the people in the different groups.”

Normally trial volunteers do not know whether they got an active vaccine or the placebo until the end of the study (in my case August), but I do wonder.

As a result of trial participation, travel and potential exposures I have now had 12 Covid-19 tests — all negative.

Despite a surge in infections around me, trips to two other African countries in November and December, and family members testing positive for Covid-19 this month, I have not been infected, unlike people close to me — who have been equally careful about wearing masks, staying outdoors and handwashing.

But at least now my anaesthetist sister — who has been assisting with intubating Covid-19 patients and doing volunteer shifts as a nurse to relieve exhausted nurses — and her neurosurgeon husband could soon get protection from this vaccine.