Health – World No Tobacco Day

4th June 2019

TB: This pee test could save your life

4th July 2019NEW YORK (360 Dx) – Tuberculosis infection is the most common cause of death for people living with HIV globally, but TB in very ill HIV patients is a challenge to diagnose using traditional methods because they typically have low levels of bacteria in their sputum, if they can produce sputum at all.

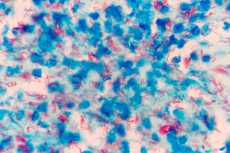

Mycobacterium tuberculosis under a microscope

To address this, Fujifilm, in partnership with the Foundation for Innovative new Diagnostics, have developed a urine-based, point-of-care TB test that also shows higher sensitivity compared to an existing similar test from Abbott.

The existing urine-based TB test from Abbott subsidiary Alere was developed to overcome issues with sputum testing, and the World Health Organization has suggested this test can be useful among HIV patients with low CD4 counts. It has also been shown to decrease mortality among very ill HIV patients. It is simple, rapid, and low cost, but unfortunately it also has low sensitivity, particularly in patients whose HIV is less severe.

In a study published last month in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, researchers found that Fujifilm’s test called Fujifilm SILVAMP TB LAM was about 30 percent more sensitive than the Alere test from Abbott.

Specifically, the study compared the two point-of-care urine-based TB tests using biobanked urine samples from patients hospitalized with HIV in South Africa. It found that the Fujifilm test had a sensitivity and specificity of 70 percent and 96 percent, respectively, compared with a sensitivity and specificity of 42 percent and 98 percent for the Abbott test.

Urine-based TB testing is a unique way to assess whether someone is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and it could be particularly useful in certain patient populations. Most TB tests detect the bacteria in sputum, but patients who are very sick have a hard time producing sputum samples, as do children. HIV-positive patients can also have low levels of bacteria in their sputum, while patients who have extrapulmonary TB infections wouldn’t benefit from sputum testing at all.

Fortunately, as part of the body’s response to a tuberculosis infection, some TB bacteria are broken down and a carbohydrate from the cell wall called lipoarabinomannan (LAM) can be excreted in a patient’s urine.

A meta-analysis of clinical data on the Alere Determine TB LAM Ag test conducted by WHO in 2014 suggested that among the sickest patients with extremely low CD4 counts, it is about 40 to 70 percent sensitive.

But in patients who are less sick, or who have higher CD4 counts, the test is down to about 15 percent sensitivity, and it “becomes pretty ineffective at that point,” according to Samuel Schumacher, deputy head of TB at FIND.

This is why WHO recommended the test for use only in a narrow range of people, “Essentially, the sickest HIV patients, who are hospitalized because they are so ill,” Schumacher said.

Still, two randomized control trials of the Alere LAM test showed encouraging results. A 2016 study looked at a large sample of 8,728 patients from 10 hospitals in four different sub-Saharan countries and showed more patients who were tested using the Alere LAM test were started on TB treatment, and started sooner, compared with those tested using only standard diagnostics. And a 2018 study showed this was particularly true for a high-risk subgroup with low CD4 counts.

Overall, the trends in the data suggest that the Alere TB LAM test could decrease mortality by around 20 percent among the sickest HIV patients, Schumacher noted.

A representative at Abbott noted in an email that the Determine TB LAM Ag test remains “an important part of Abbott’s infectious disease product portfolio.” The current product has a claim for HIV co-infected patients only, who show a diminished CD-4 cell count. The representative highlighted that in those patients the TB LAM concentration is higher and detectable by the current test. However, Abbott is working on the development of a next-generation TB LAM assay “that will allow use of the test in non-HIV patients,” the representative added.

Keertan Dheda, head of pulmonology at the University of Cape Town in South Africa who has previously evaluated the Alere test, noted in an email that the significantly improved sensitivity of the new Fujifilm assay in patients with advanced HIV is “very encouraging.”

The case-controlled study of biobanked samples should now be validated prospectively in field studies using unselected cohorts of HIV-infected patients, he said.”This is a vulnerable group with high mortality rates and difficult-to-diagnose TB,” Dheda emphasized.

In addition, Dheda is also curious to know whether the Fujifilm assay can provide any additional diagnostic utility in cases of HIV-infected outpatients, as opposed to hospitalized patients, who tend to have higher CD4 counts, or even in HIV uninfected patients who are sputum-scarce or have extrapulmonary TB.

In the future, the hope is that more patients can be tested rapidly and put on TB treatment on the same day. This would be helpful because, Schumacher said, some estimates indicate that as many as 30 percent of people who test positive for TB don’t return to get their test results, or to start treatment.

“People living with HIV have very high TB mortality rates — many of them die, and actually die very rapidly. So, having quick tests is especially important for that population,” he said.

“We have early data showing promising results in children, as well”, Schumacher said. It is currently estimated that there about 1 million new cases of active TB in children each year, and for some under the age of 5, the only way to get a sample is via hospital procedures like induced sputum or gastric aspirates, which can be a distressing experience for them.

In addition to testing the urine-based assays in children, FIND is working with partners to develop a stool-based TB test, called Stool Processing Kit, Schumacher said. That work is ongoing and is in trials currently.

The history and future of the Fujifilm LAM test

There has been a great need for better diagnostics to address TB/HIV co-infections, in part because they are so deadly.

Being immunocompromised in any way, including because of HIV infection, makes a person more likely to become infected with TB, as TB is an opportunistic infection. And, HIV infection is “the most powerful known risk factor” for TB disease progression from latent infection to active disease, Schumacher said, increasing risk of progression by twentyfold.

While the biology of co-infection is universal, in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa the rate of HIV/TB co-infection is particularly high, with more than half of all TB patients also being HIV co-infected, Schumacher said.

For example, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Global HIV and Tuberculosis the estimated HIV prevalence in Lesotho is 25 percent, but 72 percent of TB patients who have been tested for HIV are HIV-positive. In South Africa, the HIV prevalence is 18 percent and 59 percent of TB patients whose HIV status is known are co-infected with HIV. The societal cost of HIV is also high in these regions; South Africa had 100,000 HIV deaths in 2017 and 1.3 million orphaned children due to HIV.

And yet, TB can be treated and does not need to be fatal to HIV patients, even in resource-poor settings. Lesotho and South Africa also had 74 percent and 81 percent success rates in treating TB in 2015, respectively.

Although WHO declared a global TB emergency in 1993, Schumacher said there had been relatively little movement in TB diagnostics compared with diseases like HIV and malaria. In part, that has been because TB often affects the poorest people in the poorest countries. “It is really only over the past 10 or 15 years that this has started to change,” he said, and it has still proven quite challenging to develop good diagnostic tests for TB.

Tuberculosis “is a really complex disease” to develop tests for because it is compartmentalized, Schumacher said, and it is not easily found in straightforward samples like blood or nasal swabs.

There had been theories about the low sensitivity of the Alere LAM test, he said, for example that the LAM carbohydrate is only present in the urine of very sick people because they have extrapulmonary TB of the kidneys.

But, “some of the work that [FIND has] done showed that you can find LAM in probably all TB patients living with HIV, and maybe even all people without HIV,” he said.

So, FIND worked closely with WHO to define the needs for rapid, inexpensive, non-sputum tests, and, in a study FIND coauthored last year in The Journal of Clinical Microbiology, the group described the basic science of LAM and the development of new reagents that ultimately became part of the Fujifilm assay.

Schumacher said that “having the right reagents, and the right antibodies that target the right epitopes,” has been the key to developing a more sensitive and specific assay.

Once they had the reagents, the team at FIND sought out a technology platform that could enable a sensitive assay and decided the silver amplification step in the Fujifilm technology made it the best option.

FIND and Fujifilm signed a development contract for the assay in 2016, following which the group got funding from the Global Health Innovative Technology Fund (GHIT) of Japan, and began a trial of the test in October of last year.

The Fujifilm test improves upon the Alere test “in many ways,” Schumacher said.

The Alere test uses polyclonal antibodies, he said, and these are against epitopes that may not be the ideal ones. “There are other mycobacteria that also have similar carbohydrates in their cell walls,” he said, “so that is also probably why the Alere test suffers from imperfect specificity.”

The Fujifilm test uses antibody pairs discovered through FIND’s work, Schumacher said, and FIND provided all the components and antibodies for the kit. It also worked with Fujifilm throughout the tests’ development. FIND will now help Fujifilm work on validation.

Schumacher said there is also more research to be done on subjects like the complimentary value of urine-based and sputum-based tests, for example using the LAM tests and the Cepheid GeneXpert tests.

“They may potentially pick up different populations, and there may be incremental value in using those tests together as well,” he said.

And, urine tests that detect carbohydrates can’t tell anything about mutations or drug resistance, he said, so a molecular test will still be important.

According to its website, other non-sputum tests in FIND’s diagnostics pipeline include immunoassays from Salus Discovery, NanoPin, Global Good, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and breath-based tests from Rapid Biosensor Systems, Breathtec Biomedical, Avisa Pharma, and the eNose Company. The non-profit is also guiding development of many nucleic acid amplification-based tests for TB.

FIND is already working on next-generation LAM tests, Schumacher said, adding he is aware that other groups are doing the same as well, and he anticipates more LAM assays in the future.

The FIND team expects to be publishing more data over the coming months on the Fujifilm assay, including data on HIV outpatients, HIV-negative people, children, and patients with extrapulmonary TB. The team also presented current data to WHO a few weeks ago, Schumacher said.

FIND will be starting a large prospective multicenter study of the Fujifilm LAM test in the intended settings of use, and the non-profit is requesting applications for additional partners for these studies.

“All of that will go to WHO again for them to assess and make global policy recommendations,” he said.

That will likely happen sometime next year when the additional data have been generated. A representative at Fujifilm noted in an email that, together with FIND, the company will be continuing to develop the TB LAM kit “with the aim to acquire a recommendation from the WHO.”