Health Feature: hay fever and seasonal allergies

20th September 2018

UCTLI celebrated Heritage Day (National Braai Day)

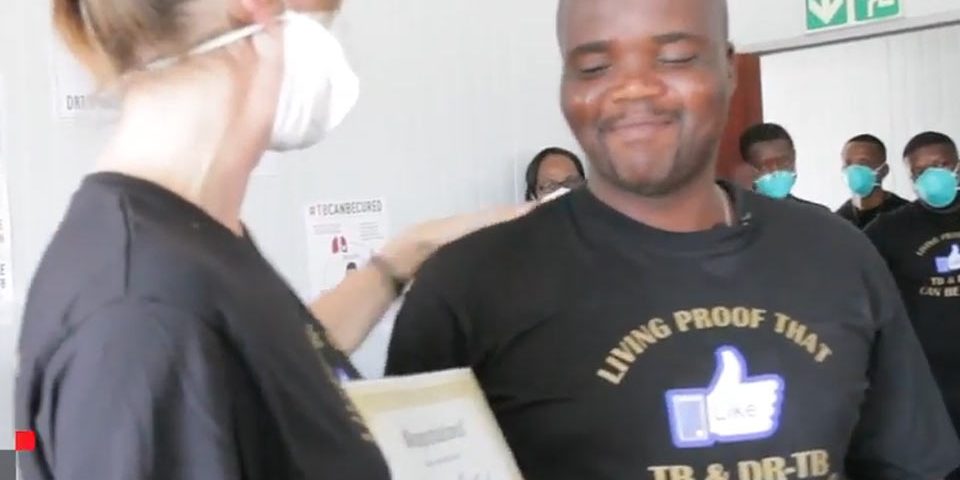

26th September 2018The story of Goodman Mkhanda

In the world of tuberculosis it is often said that ‘it takes a village to cure TB’, and in the case of 36 year old Goodman Mkhanda from Khayelitsha in South Africa’s Western Cape Province, this was no exaggeration. Goodman, who was declared cured of extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) in December 2017, walked a longer and more varied treatment journey than most – four years from his diagnosis to his cure, in contrast to the span of traditional treatment, which can last anything from 9 -24 months. As his treatment failures and disappointments stacked up, so his village grew.

In the first six months of his treatment for drug resistant TB (DR-TB), Goodman was informed that he was sputum culture negative – an indication that his treatment would ultimately be successful. However, after 21 months of arduous treatment his sputum once again tested positive for TB. He was, in his words, ‘back to square one’, and in early 2014 was diagnosed with XDR-TB.

His type-2 diabetes, diagnosed in 2008, significantly complicated the management of his treatment. According to Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology medical journal (2014), “Patients with concurrent diabetes suffer worse tuberculosis treatment outcomes, a higher rate of relapse following tuberculosis treatment, and a higher risk of death from tuberculosis than patients with tuberculosis alone.”

Goodman, however, was determined to fight on, and so were his doctors. Repurposed DR-TB drugs like Linezolid and Clofazamine were added to his treatment regimen, and in May 2014 Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) helped Goodman to access the new DR-TB drug bedaquiline, one of only two new DR-TB drugs developed in the last 50 years. Goodman had spoken out about the arduous nature of the standard DR-TB treatment – especially the painful and toxic injection he received daily for 9 months (3 months longer than the standard period at this time). When he learned that the new medicines he was being offered were not available to most other DR-TB patients in South Africa and elsewhere, he added his voice to the growing global call on governments and international standard setting bodies to get DR-TB patients access to simpler, faster, more effective DR-TB treatment regimens, using new and re-purposed DR-TB drugs. Goodman did this in spite of the fact that TB continued to show up in his sputum, even after he became the first person in Khayelitsha to access delamanid, the other new DR-TB drug.

One of Goodman’s doctors – Dr. Jenny Hughes, formerly with MSF in Khayelitsha – sat Goodman down to a difficult conversation.

“I said, talk to your pastor, or whoever it is you need support from if this treatment doesn’t work, and he said, Are you saying I’m going to die? and I had to say, yes, I think so.”

Goodman refused to accept that he was out of options

“Can’t you cut it out?” he asked his doctors, and inspired by his resolve and his spirited activism, in 2016 Goodman’s doctors reached out to surgeons at the the Pulmonology Division at Groote Schuur hospital, who agreed to scan his chest. The scan revealed a lump on Goodman’s left lung.

“It was clear that he had disease that was confined to a cavity in the left side of the lung, and that the medication he was taking was just not getting in to that part of the lung. We decided with him that surgery might be a better option, to try and remove this part of the lung,” said Dr. Ali Esmail, Goodman’s surgeon.

The lump was removed, and a port was installed in his chest through which a high strength antibiotic called Merropenem would be injected twice a day. Merropenem belongs in the WHO Group 5 drugs for DR-TB, but an extremely high cost and the fact that it can only be taken intravenously means it is rarely used to fight DR-TB.

MSF covered the cost of a six-month course of Merropenem for Goodman, who was taught how to inject himself so that he could leave the hospital and continue treatment at home. According to his Department of Health doctor, Dr. Daine James, “this is not common practice, because the risk of infection is so high, but it is testament to the type of guy Goodman is – disciplined and highly informed about this condition – that he was allowed to inject himself.”

On 17 December 2017 Goodman was rewarded for his never say die attitude – the Goliath of XDR-TB was declared dead. Goodman, very much alive, was declared cured.

His story is one of outstanding personal bravery and resilience, but it also shows up the fact that access to the best diagnostic tools and the newest and most effective medicines is simply not enough for some TB patient. To speak of the 1.6 million people who die each year from TB is to speak about Goodman. Greatly increased funding is urgently required for the development of critical new TB tools and medicines, so that doctors are able to more effectively fight and cure this ancient and deadly disease.

MSF AND TB:

MSF is the largest non-governmental provider of DR-TB treatment worldwide. MSF is involved in research for new, shorter and more effective drug regimens, conducting both clinical trials and observational research in some of its DR-TB treatment projects.

In South Africa:

MSF supports access to new and re-purposed drugs for strengthening DR-TB treatment regimens in Khayelitsha, Western Cape (since 2007) and in Eshowe & Mbongolwane, KwaZulu-Natal (since 2017), where MSF also partners with the local department of health on TB detection and active case find strategies.

MSF is also a partner in two multinational drug-resistant TB clinical trials that have research arms in South Africa – TB PRACTECAL in KwaZulu-Natal, near Durban, and endTB in Khayelitsha, Western Cape province. Both are phase III trials, and aim to find a treatment regimen for DR-TB that is drastically shorter, more effective, does not require patients to have painful daily injections that are toxic.

Read more, Doctors without borders SA, 25 September 2018